Contribute

| South Asian Art - In Memory Of Prashant H. Fadia |

Pedro Moura Caravalho, Anne Hawley and Alan Chong

04/16/2008

Lisbon had been the main trading center in Europe for Asian commodities since the discovery of the maritime route to India. The earliest goods made in India to the order of a Portuguese patron must have been commissioned soon after the arrival of the Portuguese. These objects were probably copied from Western models. Sixteenth-century sources documenting the arrival in India of Western artworks or decorative objects are rare. Objects were brought as personal belongings of the privileged classes who settled abroad, and occasionally as gifts for local rulers. Portuguese political, military, and religious authorities as well as wealthy merchants and commercial agents from Portugal and other European countries carried various types of goods to India.

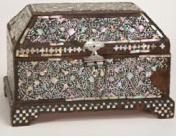

Surviving Indo-Portuguese objects fall into three broad categories: those made in India following European models and therefore intended explicitly for the European market (such as the Sri Lankan ivory casket and the Bengali wall hanging); those in local form but decorated with European motifs (the Bengali chair); and those in local form that then received Western-style mounts in either Portuguese India or Europe. Additionally, some objects of Indian form and decoration are often categorized as Indo-Portuguese because they resemble works from the categories above (a Gujarati casket is an example of this).

As early as 1498, Vasco da Gama offered a “chair furnished with pile velvet, rich, and decorated with gilded silver nails†to the ruler of Calicut. Earlier on the same voyage, the captain of a vessel in Vasco da Gama’s fleet had presented a chair with crimson and silver nails to the king of Malindi, in Kenya. It is uncertain whether Vasco da Gama and his men always intended to use such chairs as diplomatic gifts or whether they were simply conveniently on hand. The chair given to the ruler of Calicut seems to have been of some importance and may have belonged to Vasco da Gama himself.

Most of the Western objects Indian artisans re-created in the early sixteenth century were probably utilitarian. However, a few years after the conquest of Goa, more refined works were being exported. Sometime before 1515, Afonso de Albuquerque received a “table with its feet, all covered in gold†from a local ruler to be sent to D. Manuel I. This seems to describe a campaign table, composed of a folding top and collapsible legs, which became common in Portuguese India. If correct, this is the earliest record in the Early Modern period of any object copied in Asia from a Western prototype.

Much as one would expect, the 1522 inventory of D. Manuel I’s possessions lists several objects from India, including works of Western design. Two “incense-boxes of Indian wood painted in black†may or may not have been based on European models, but another item was certainly informed by Western aesthetics: “a small silver box that came from India; the top of its lid being carved with Roman [Renaissance?] work.†This silver box perhaps received particular attention from the author of the inventory because it was among the first such precious objects to arrive in Europe; most inventories of this period are extremely vague in the description of forms and materials. Even the meaning of “India†was imprecise and confusing from the sixteenth century on, often simply meaning “oriental.â€

Illustrating this variety of artistic exchange in Indo-Portuguese objects are two low Indian chairs that must have reached Lisbon in the middle of the sixteenth century before making their way to the Spanish court. In 1568 the Italian painter Federico Zuccaro depicted one of these in his monumental Annunciation altarpiece made for the Escorial near Madrid. The chair is Indian with no apparent European influence; its inclusion in such an important painting demonstrates the taste for such exotic objects. By contrast, a roughly contemporary chair that is also Indian in form, the so-called “cadira de la reina,†is decorated with Renaissance elements clearly inspired by Western models.

In the early sixteenth century, Indian artisans produced works at the Portuguese court itself. Although the presence of such craftsmen is well documented, not a single object made by them has been identified. Between 1518 and 1520, an Indian goldsmith named Rauluchantim crafted objects “made in the fashion and use of India†while in the service of D. Manuel I in Lisbon. Afonso de Albuquerque sent a group of female embroiderers, possibly from India, to Portugal by before 1515. Although their ship, the Flor de la Mar, sank off the Malacca coast, it is possible that other such

groups reached Portugal.

While the Portuguese valued Indian artistic innovations in terms of form and style, they were clearly beguiled by the luxurious materials used in many Indian objects. D. Manuel I owned a casket and a tray decorated with mother-ofpearl, a material completely unknown in Europe. His taste for such objects was shared by the privileged classes in Portugal and throughout Europe, where they were often incorporated into princely curiosity cabinets. As early as 1529, the French king Francis I was sent from Lisbon a chalice made in India, the surface of which was decorated with mother-of-pearl. Between 1532 and 1534, one of Francis I’s royal goldsmiths, Pierre Mangot, added mounts to two mother-of-pearl caskets from Gujarat; one of these is in the cathedral of Mantua, the other in the Louvre.

Elaborate caskets such as these were reserved for rulers, but not only of the Western world. A miniature of the 1520s in one of the most magnificent Iranian manuscripts ever produced, the Shahnama illustrated for the Safavid ruler Shah Tahmasp I, suggests that Islamic rulers also had access to works decorated with mother-of-pearl. In this miniature, the painter Mirza ’Ali depicted a Hindu envoy presenting Shah Nushirvan with a casket of the same form as that in the Louvre. However, the illustrated casket seems to have decoration similar to that of the example in the Gardner Museum, which is covered with Gujarati lac and inlaid with mother-of-pearl.

Mother-of-pearl was only one of the precious materials used to decorate luxury objects in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Tortoiseshell, lacquer, and ivory were also employed in production centers under Portuguese rule or influence. With the decline of Portuguese power and consequent loss of many of these establishments, however, less exotic materials grew in popularity. In the late seventeenth and eighteenth century, pieces of furniture decorated with dark shisham wood inlaid on honey-colored teak became quite common. While inlay techniques can

provide pleasing results when used imaginatively, designs were often repeated, revealing a lack of creativity typical of later objects. Nonetheless, Indo-Portuguese works continued to circulate in Europe, as seen in two of Johannes Vermeer’s paintings of the 1660s that depict small cabinets. The inclusion of a distinctly Indo-Portuguese object reflects the taste for the exotic characteristic of many seventeenth-century Dutch paintings.

Royal inventories and the survival of objects directly attributable to princely collections tend to suggest that only the ruling classes had access to exotic curiosities. This is certainly the case for sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century works fashioned of precious materials, but there are indications that pieces made with less costly materials were within

reach of large segments of Portuguese society from the mid-seventeenth century onward. Beginning in the late 1500s, merchants specializing in Asian articles made such works available in provincial towns. Although furniture was quite scarce in Lisbon households during this period, many works are described as having an Indian origin; some of these are recorded in more modest inventories. This partly explains the strong Asian influences observed in Portuguese decorative arts, notably in textiles and ceramics beginning in the seventeenth century. The existence of goods from China and India – including large numbers of textiles, ivories, pieces of furniture, and objects made of mother-of-pearl and tortoiseshell – in ecclesiastical and private collections throughout Portugal indicates that a growing number of people could afford them.

You may also access this article through our web-site http://www.lokvani.com/

Chair, Bay of Bengal, 16th Century

Casket, Srilanka, probably Kotte, ca. 1550

Casket, Gujarat, ca. 1600