Contribute

| Museum Of Fine Arts, Boston, Showcases Vibrant Hindu Prints |

01/28/2026

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Showcases Vibrant Hindu Prints Rarely Shown in the U.S. Vivid prints of divinities are part of daily life for Hindus in India and around the world, used for worship in homes, factories, and offices, as well as for adornment on cars, calendars, computers, and shop counters. Organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), Divine Color: Hindu Prints from Modern Bengal explores the origins of these popular prints—which have historically been overlooked by the art world—and their powerful impact on Indian pop culture, religion, and society. The exhibition is the first of its kind in the U.S., focusing specifically on the radical creation of these works by Bengali artists in 19th-century Calcutta (today Kolkata, West Bengal). The MFA is one of only two American museums that collect these rare early prints—those that survive represent only a fraction of the thousands that were originally produced—and the exhibition presents nearly 40 vibrant examples. Featuring more than 100 objects in total, Divine Color also includes other prints, paintings, sculptures, and textiles from the MFA’s South Asian collection as well as select loans. The exhibition is on view from January 31 through May 31, 2026, in the Lois B. and Michael K. Torf Gallery, and is included with general admission. It is accompanied by a catalogue, produced by MFA Publications, featuring scholarly essays and stunning reproductions of nearly 50 rare lithographs. Divine Color is organized by Laura Weinstein, the MFA’s Ananda Coomaraswamy Curator of South Asian and Islamic Art. “I’m excited for our visitors to experience these remarkable works, which add an important perspective to the South Asian collection at the MFA,” said Weinstein. “These vibrant images illustrate the creativity, innovation, and skill of Bengali artists during colonial rule, and their contemporary iterations remain prevalent today in India and the Indian diaspora—including here in Boston. Their enduring presence is a testament to their visual, ritual, commercial, and political power.” Exhibition Overview The opening section establishes how artists pioneered new forms of sacred art for personal use in Calcutta during the late 1800s. At the time, the city was the capital of British India and a center of new goods, technologies, and markets. Bengali artists took up lithography—a printing technique invented in Germany—to produce images of the gods that were more affordable, realistic, and colorful than ever before. Works such as Shri Shri Krishna Balarama (about 1910–1920) offer an example of artists’ maximalist approach—utilizing imported colored inks to form shapes and figures, juxtaposing bright hues for striking effect. Additionally, a short film produced by Peru Films shows the ubiquitous presence of modern prints of the gods in Calcutta today. The second section, “The Context of Calcutta,” which includes an interactive digital map developed by the MacLean Collection, orients visitors to the city at the time lithographic prints first emerged. The local Bengali population played a key role in keeping 19th-century Calcutta culturally and economically productive, as did people from other parts of the Indian subcontinent who flooded into the city in search of opportunity. In addition, Portuguese, Greek, Armenian, and Chinese immigrant communities contributed to Calcutta’s flourishing industries and culture. Objects and artworks from this period reflect the cosmopolitan nature of the population, and their many different—and sometimes clashing— perspectives and priorities. Art Studio (Calcutta, active about 1890–about 1912). “Lithography in Bengali Hands” examines the different lithographic techniques that artists used to make and reproduce divine imagery with a new level of intricacy, color and elaborate backgrounds. Some Bengali artists learned in presses run by Europeans, while others learned European pictorial techniques at the Government School of Art, run by the British. Some began their careers making watercolors that are known today as Kalighat patas or paintings—a style that emerged in an area of Calcutta near the city’s temple to the goddess Kali. These different kinds of training meant that artists came to lithography with different backgrounds, sensibilities and inspirations—all of which are reflected in their works. A display in the center of this gallery, developed in collaboration with printmaking faculty from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University, offers an interactive way to explore the multistep process involved in the creation of a print. "Prints in Use: Devotion, Storytelling, Decoration” explores how Bengali prints are used in homes, where people engage with images of Hindu gods in many ways, most prominently through intimate expressions of devotion. Four displays in the center of the gallery mix and match prints and sculptures to evoke domestic shrines that are reflective not just of religious ideas but also family history, community beliefs, and personal taste. An audio experience in each corner of the gallery explores how love, care, and devotion to the gods also comes alive through storytelling, poetry, and music. Three sound stations present recordings read by members of the local Bengali community. These modes of expressing devotion were transferred to the nation itself in the late 1800s, as the movement for Indian independence grew. The section “Goddesses and Homeland” explores how some deities became emblems of national identity and anticolonial resistance. Nationalist leaders pledged allegiance to Kali, who is associated with the destruction of ego and ignorance. Durga became symbolic of the motherland, inspiring hope as a defeater of demons and wielder of powerful weapons. Bengali groups fighting for independence invoked Chinnamasta as a symbol of heroic fearlessness and sacrifice for the nation, while Annapurna, “the giver of rice,” took on additional meaning due to her association with the welfare of the populace. The political connotations of these goddess prints were only occasionally explicit, but they were widely understood by those who purchased, displayed, and used them. The final section, “Beyond Calcutta,” explores how access to print technology expanded after the 19th century, transforming India’s visual landscape forever. A method called offset printing increased the speed of production, and by the end of the century, artists designed Hindu god images on computers and printed them digitally. Subject matter expanded as well. Devotional and educational images for Muslim, Sikh and Jain populations joined the existing repertoire of Hindu images. Printing houses churned out posters for public figures, political parties, and campaigns, as well as advertisements for movies, television, and products. The exhibition culminates in an immersive room featuring wall-sized collages of these popular images from the 20th century, developed in collaboration with the Delhi- based Tasveer Ghar—an organization dedicated to collecting, digitizing, and documenting South Asian popular visual culture. Publication The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue from MFA Publications, which restores these Hindu prints to their rightful place in the history of Indian art. The book invites readers to experience not only the divine world of Hindu gods but also the shaping of a modern visual India, featuring scholarly essays and stunning reproductions of nearly 50 rare lithographs. Public Programs Divine Color is accompanied by a four-session course (Thursdays, March 5–26) exploring Bengali art and culture. Course speakers include exhibition curator Laura Weinstein; Brian Hatcher, Packard Professor of Theology at Tufts University; Susan Bean, an independent scholar and former curator of South Asian and Korean art at the Peabody Essex Museum; and Sugata Bose, Gardiner Professor of History at Harvard University. Additionally, Looking Together sessions (Wednesdays, April 8, 15, and 29) offer opportunities to explore the exhibition with the curator in a small group setting. Sponsors Support is provided by the William Randolph Hearst Foundations, Nalini and Raj Sharma, and the Dr. Robert A. and Dr. Veronica Petersen Fund for Exhibitions. About the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston The MFA brings many worlds together through art. Showcasing masterpieces from ancient to contemporary, our renowned collection of more than half a million works tells a multifaceted story of the human experience—a story that holds unique meaning for everyone. From Boston locals to international travelers, visitors from all over come to experience the MFA—where they reveal connections, explore differences and create a community where all belong. ### Open six days a week, the MFA’s hours are Saturday through Monday, 10 am–5 pm; Wednesday, 10 am–5 pm; and Thursday–Friday, 10 am–10 pm. Admission is $30 for adults; $14 for youths ages 7–17; and free for University Members and youths ages 6 and younger. The Museum offers $5 minimum, pay- what-you-wish admission after 5 pm on the third Thursday of every month, as well as free admission for Massachusetts residents on four open houses throughout the year (Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Memorial Day, Juneteenth, and Indigenous Peoples' Day). Plan your visit at mfa.org.

You may also access this article through our web-site http://www.lokvani.com/

Shri Shri Krishna Balarama (about 1910–20), published by Kansaripara Art Studio.

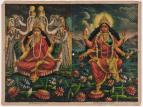

Kamala and Bhairavi (about 1885–95), printed and published by Calcutta Art Studio (active 1878–1905).

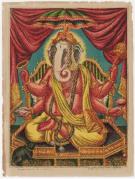

Ganesha (about 1895–1900), published by Amar Nath Shaha (Indian, 1800s) and printed by Chore Bagan