Contribute

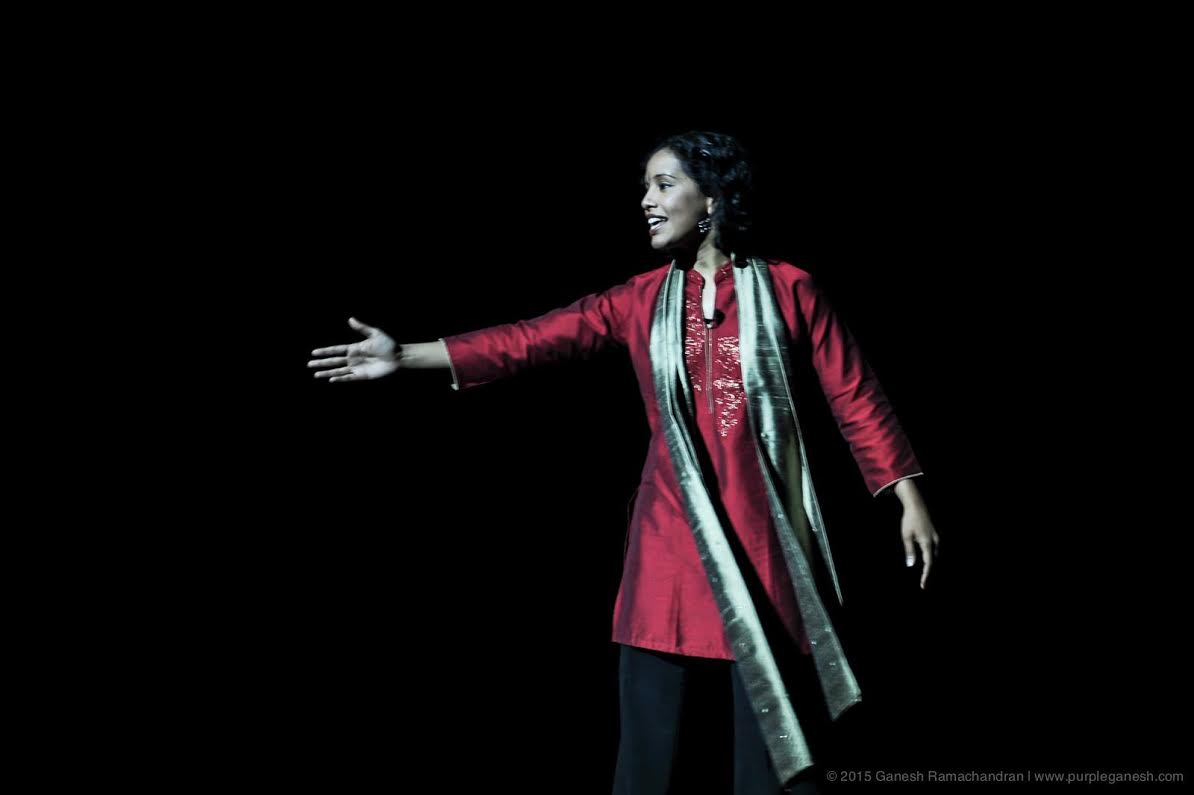

| Lokvani Talks To Dr. Smitha Radhakrishnan |

Ranjani Saigal

08/25/2015

(This article is sponsored by New England Shirdi Sai Temple)

Thank you for your wishes. And yes, I very deliberately have named this a studio and not a school. I think of NATyA Dance Studio (NDS) as opening up a new space to learn and practice Bharatanatyam. This space aims to develop a love for the art, and a love for self-expression through the body for all who participate, whether through classes or open studio. I hope this new space helps to build a performing arts community, so I invite students as well as other dancers to come share it. Classes are just one part of it.

You are a very busy faculty member. What motivated you to start NDS?

From the age of 3, my daughter was completely captivated by Bharatanatyam videos. I was happy to indulge her. I quickly noticed she wasn’t very interested in the pieces that were very athletic, no matter how perfect the form. She wanted to watch the padams and javalis, and certain parts of the varnams, all of which told stories. And she actually understood a great deal about the stories, without any explanation. I wondered if maybe kids that age were somehow naturally theatrical and interested in stories. She hadn’t figured out the difference between what was imaginary and what was real, so what she saw being depicted in dance was not acting, it was real for her. I thought that was magical.

In the spring of 2013, I taught dance at my daughter’s preschool. This was a mixed class of girls and boys, and my daughter was the only Indian child. I taught them a dance I made up about the springtime and invited the children to come up with movements to depict the trees and the wind and the flowers. They had great ideas! Simple Bharatanatyam gestures and movements were the base, but the kids improvised a lot of the gestures themselves. I would organize their ideas into a sequence, and they all felt like choreographers. It was a lot of fun, and I got so much positive feedback from parents about how much their kids were enjoying the classes. It was an experiment for me, but it was inspiring.

Since then, I’ve been waiting for the right moment to create a space where I could do what I did at the preschool in a more formalized way. I think the moment is finally here! I’ve received a lot of positive feedback when I’ve pitched the idea to former teachers and other dancers, and that has been a great motivation too. I have a lot to share and am ready to put it out there. I’m initially aiming the classes at little kids, but am happy to take on older students and adults too.

You are a second-generation dance teacher. How do you view dance education differently from your teachers?

I’m not sure that just being born in the U.S. would necessarily make me have a different teacher, but I have had different life experiences than most immigrant Bharatanatyam teachers. Wherever I have done fieldwork for my sociological research, I have found a way to make dance a big part of my life, and that was true when I worked in South Africa, Mumbai, and Bangalore. Wherever I have lived since childhood—Phoenix, Berkeley, Boston—I have integrated myself into a community of Bharatanatyam dancers. I have learned from amazing teachers, performed, taught, and produced original work too.

My training as a sociologist has also deeply influenced my understanding of Bharatanatyam because it has given me a historically grounded, scholarly basis for understanding how and why our South Asian community thinks about Bharatanatyam mainly as a way of keeping in touch with Indian culture for girls. I am grateful for that approach. My initial introduction to dance occurred because of it. But I also find that approach limiting. I hope to promote the idea that Bharatanatyam is a powerful language for artistic self-expression that not only puts us in touch with Indian cultural heritages, but also allows us a way to connect with ourselves, with each other, and with our broader communities, within and beyond the South Asian diaspora.

You have had an unusual career path for a South Asian: Dance and Sociology. How did you choose these fields?

Just by putting one foot in front of the other, listening to my teachers and my own inner voice! Although my parents were always concerned about me being able to support myself and have a good job, they were open to the idea that I might find something outside of the fields they were familiar with. So that was a big help.

Dance has been in my life for as long as I can remember, but sociology is what I chose as an adult. I chose the discipline because it provided me with a profound, intellectually satisfying explanation of the world I observe and experience. I am still amazed by the power of a sociological perspective to help look beyond what seems obvious, and that is very important to me. I chose a career in academia because, by some miracle, I could! If I had not been lucky with graduate school admissions and fellowships, I would have done something else, and that would have been fine too, I’m sure. I consider myself quite lucky to have stumbled upon a profession I love, and I’ve enjoyed the symbiotic relationship that sociology and dance have in my life.

What has been the greatest opportunity that dance has provided you?

It’s hard to pick just one because dance has defined my life experience at every stage, so I have to pick the most recent. The last seven years with Navarasa Dance Theater have been the greatest, truly. Aparna Sinchoor and Anil Natyaveda are masters of their forms and true professionals who work harder than just about anyone I know. I thought I knew what it meant to do professional work in dance. And then I started working with them, and found out I knew very little! I have learned a ton and I continue to learn with them and perform when possible, which is harder now that they live in Los Angeles. Especially the big shows we have done together—in Montreal, Cambridge, New Jersey, New York City, St. Louis, and Los Angeles—have been so memorable. I also think that learning from Katherine Kunhiraman as a graduate student in Berkeley is right up there with life-defining amazing dance opportunities.

How has the Indian American culture evolved since you were a youngster?

I am struck by how highly visible and mainstream Indian American people are today. I hear Indian voices and names on the radio all the time, in the news, online, everywhere. People know what Bollywood is. Most people even know what Indian classical dance is! That was never the case when I was growing up. I always quote a close friend of mine who once said “I was Indian before it was cool.â€

Indian kids growing up today don’t seem to face the kind of marginalization from mainstream white American culture that I felt growing up, at least in large U.S. cities. I see kids living in one culture that integrates Indian and American aspects, along with the cultural aspects of other immigrant communities, and that’s wonderful. I do hope it doesn’t go to the opposite extreme, however, where Indian communities isolate ourselves from the mainstream entirely just because there are so many of us now. I think that’s dangerous and I see it happening sometimes.

Any advice to parents who are trying to bring up children in two cultures?

I personally believe that there’s no reason to look at Indian and American culture as discrete from one another. Just the fact we are all here suggests a relationship of exchange and mutual influence. There is a long and rich set of exchanges that have taken place between India and the U.S. For example, leaders of the American civil rights movement were influenced profoundly by Gandhi’s philosophies and achievements. Yet, our communities seldom speak up in solidarity with civil rights struggles that are so pressing today. Some of the earliest Indian migrants to the U.S. were Punjabi farmers in California who married Mexican women and created their own culture, and that was over 100 years ago. We’ve forgotten that history in most Indian immigrant communities that I see.

That said, I have no idea what the best way is to bring up kids! I’m working on that myself, so if anyone has any great advice, let me know. I think it’s a real challenge to bring up kids in a way that feels true to my values as a parent while also taking into account what will best prepare kids for the world ahead. I’m on the one-day-at-a-time plan for now!

You may also access this article through our web-site http://www.lokvani.com/